Blog: Nordic Green Youth Summer Summit – a journey with the Green Youth to learn about the Sámi people and the green transition

This summer, nearly 70 young activists gathered in Åland to learn about the green transition and the Sámi people. Participants came from Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. Some of the participants were long-time party activists, while others, like me, were learners who were inspired by the topic and not affiliated with the Green Youth. The main organizer of the Nordic Green Youth Summer Summit was the Finnish Green Youth, but the event was organized in collaboration with Grön ungdom (Sweden), Grønn Ungdom (Norway), Socialistisk Folkeparts Ungdom (Denmark), and Hållbart initiativ (Åland). The project was funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers, the Young European Greens and the European Union.

The theme of the trip was green transition and indigenous peoples, which in the Nordic context meant the Sámi people. Climate change is a double-edged sword for the Sámi. While the Arctic is warming four times faster than the global average and the Sámi have reported the effects of climate change on aspects such as reindeer herding, the so-called green transition also reproduces colonialism against the Sámi in their homeland, and the Sámi have used the terms black transition or green colonialism to describe this.

Preparing for the trip by spotting windmills from the ferry and reading the orientation package.

In keeping with the common Nordic theme, we began our journey by familiarizing ourselves with various forums for Nordic cooperation, such as the Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers. As Sápmi is located in three Nordic countries, it is important that issues relating to the region can be discussed in joint Nordic forums. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the Sámi do not have their own representation in the Nordic Council, but the Sámi Parliamentary Council currently has an extended observer status.

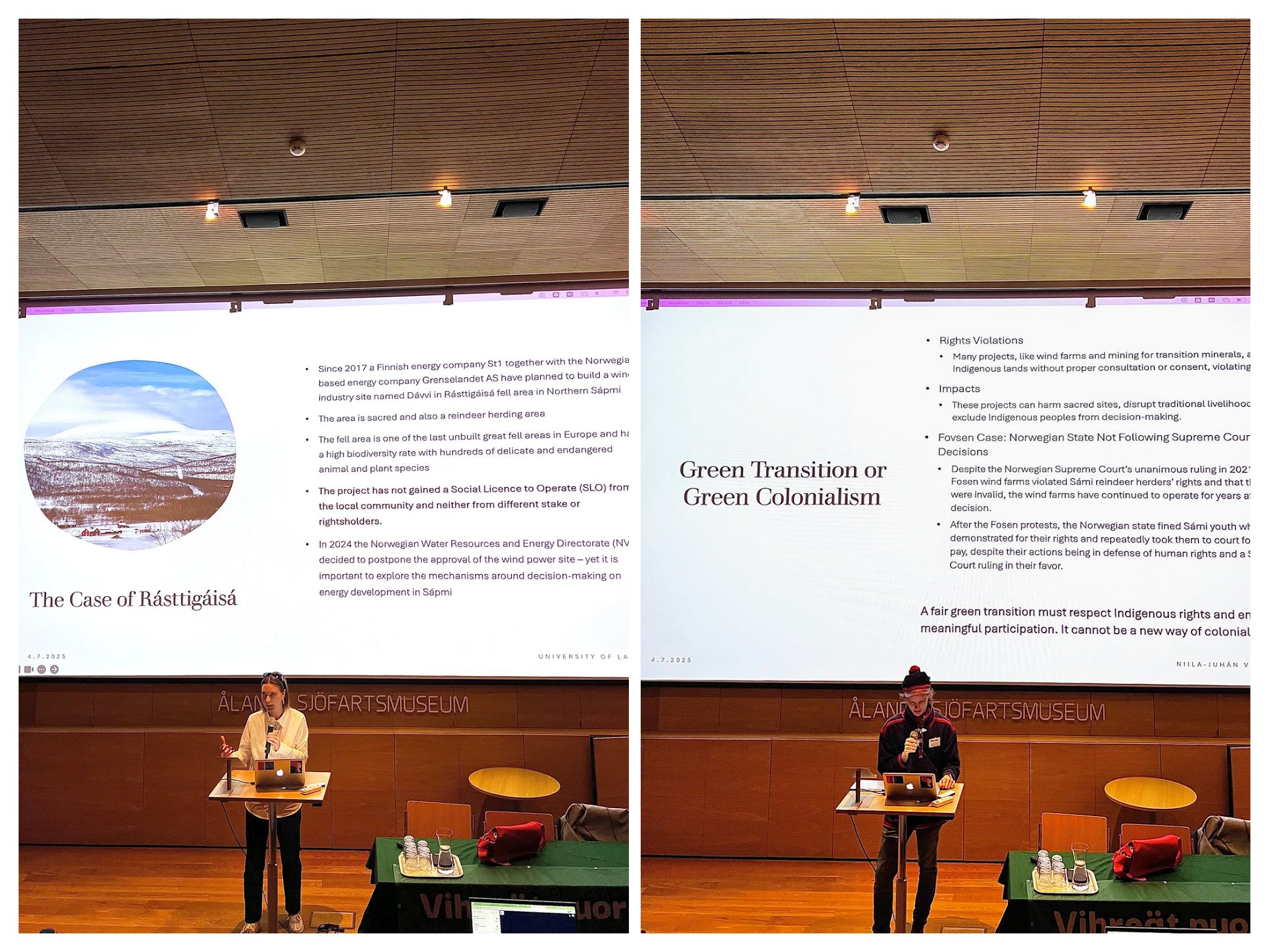

The following day, we were able to delve deeper into Sámi issues. The day’s lectures were given by Niila-Juhán Valkeapää, secretary of the Finnish Sámi Youth and vice-chair of the Youth Council under the Sámi Parliament in Finland, and Eleonora Alariesto, a master’s student in Arctic World Politics at the University of Lapland and project planner for the MÁHTUT research project. The day began with Valkeapää’s comprehensive introduction to the stages and effects of colonialist policies targeting the Sámi people. The lecture covered topics ranging from the assimilation of the Sámi people to the impact of border closures and taxation. Current challenges were also highlighted, particularly those related to the green transition and the processes (FPIC) that should be followed in these situations.

In Eleonora Alariesto’s presentation, we had the honor of hearing personal stories from her family and getting a glimpse of her unpublished research. We learned about Sámi cultural environments (SCE), where the material and immaterial dimensions meet. These places are steeped in traditions such as reindeer herding and fishing, as well as intergenerational knowledge, stories, yoiks, cosmologies, and relationships with ancestors and spirits. Alariesto’s research deals with contamination and how subjective and culturally bound experiences influence people’s thoughts and behavior, thereby also shaping perceptions of what is considered a contaminant. Different systems have different norms and categories for what kinds of things and objects belong where. In the context of Sápmi, contamination can mean, for example, irresponsible tourism or the placement of wind power in Sápmi. One of the examples discussed was Äijih in Inari. Äijih is a positive example in that the area has been restored by removing the stairs built for tourists and many tourism companies have stopped landing on the island.

Eleonora Alariesto and Niila-Juhán Valkeapää giving a lecture.

Through the categories of contamination, cleanliness, and dirtiness, Alariesto creates an interesting dichotomy between the ideas of clean wind power and dirty Sámi people. Through racial theory and colonialist research, the Sámi have been portrayed as dirty. By questioning racist and colonialist definitions of dirtiness, hegemonic notions of cleanliness can be challenged through a decolonial lens. Alongside wind power, which is presented as clean, it is also important to note how many Sámi traditions are based on the seasons and the cycle of nature, making the Sámi experts in the circular economy in today’s era of green transition and circular economy. This is also the basis for the MÁHTUT project led by the University of Lapland, in which Alariesto works as a project planner.

In addition to lectures providing historical and theoretical background, Valkeapää and Alariesto also introduced us to various Sámi actors, such as the Sámi Council, and highlighted the opportunities for Sámi people to influence non-Sámi parliamentary bodies, such as the European Parliament. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) was also included in the presentation, as there are fears that faster processing could lead to more conflicts in Sápmi, where consultation with the Sámi people in the planning and implementation of projects has previously been deemed insufficient. The lectures reviewed examples of projects where FPIC has not been implemented. One of these was the Fosen wind farm, which I am very familiar with as I discussed it in my master’s thesis. In Fosen, local Sami sidas filed a lawsuit against the wind farm, but the Norwegian government did not halt the project despite a request from the UN. The legal proceedings came to an end in 2021, when the Norwegian Supreme Court ruled that the building permit was invalid, with the farm already in operation. The government’s inaction in rectifying the situation led to widespread protests.

Later in the afternoon, the program continued in the form of a panel discussion. In addition to Valkeapää and Alariesto, the panel included Green Party MP Jenni Pitko, Norwegian Green Party politician and psychologist Hildegunn Seip, and Aili Keskitalo, former chair of the Sámi Parliament (Sámediggi, Sametinget) who currently works as a political advisor for Amnesty International Norway. The panelists answered questions that had arisen during the day’s lectures.

Aili Keskitalo also joined the afternoon panel, and I had the opportunity to take a photo with her.

One of the most important concepts in the lectures and panel discussions was FPIC, which has already been mentioned a couple of times in this text. The term comes from the English words free, prior, informed, consent. In accordance with this policy and principle, projects located in Sápmi should obtain the free, informed, and prior consent of the Sámi people. FPIC is based on Article 10 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and also appears in other international agreements.

In order for a project located in Sápmi to be socially acceptable and not (green) colonialism, it must comply with the FPIC principle. When a question was raised later in the panel discussion as to whether the Sámi should have a right of veto when planning projects in Sápmi, Aili Keskitalo considered compliance with the FPIC process to be a better option than a right of veto. In this case, the process provides an opportunity for negotiation to find ways to implement projects without rejecting them outright.

Another important issue raised during the panel discussion was the knowledge gap. The panelists discussed, for example, how many people do not really understand what indigenous peoples mean and how indigenous peoples and their rights differ from other minorities. The history of the Sámi people and other land use in the Sápmi must be understood in order to better understand the current situation. The lack of knowledge is a structural problem, which should be addressed by reviewing the existing structures and establishing a joint table for discussion with the Sámi people. The Sámi cannot solve this problem or build the table alone. Akordi also has the opportunity to support the Sámi in disseminating information. For example, in September we are organizing training on fair sustainability transition in the Sámi homeland with a focus on FPIC (in Finnish).

Although increasing knowledge is important, there are also contradictions inherent in this idea. The Sámi do not necessarily want to, nor do they need to, share all their knowledge. This applies in particular to knowledge about sacred sites, among other things. However, this can cause difficulties, as it can make it harder to protect sacred sites and show them special respect if their location is not known. However, it is important to note that the sharing of information must also be based on the consent of the Sámi people and on accurate information.

It is difficult to summarize such a broad discussion in a meaningful way, and much is inevitably left out of this text. To highlight one more point, I would like to mention the Sámi concept of birget, which Ali Keskitalo brought up in the discussion. Birget means coping in a changing environment. According to Keskitalo’s description, this principle also includes not consuming more resources than necessary. It is important to get by, but also to leave opportunities for future generations. This way of thinking could be respected more broadly when we consider a more equitable sustainable transition.

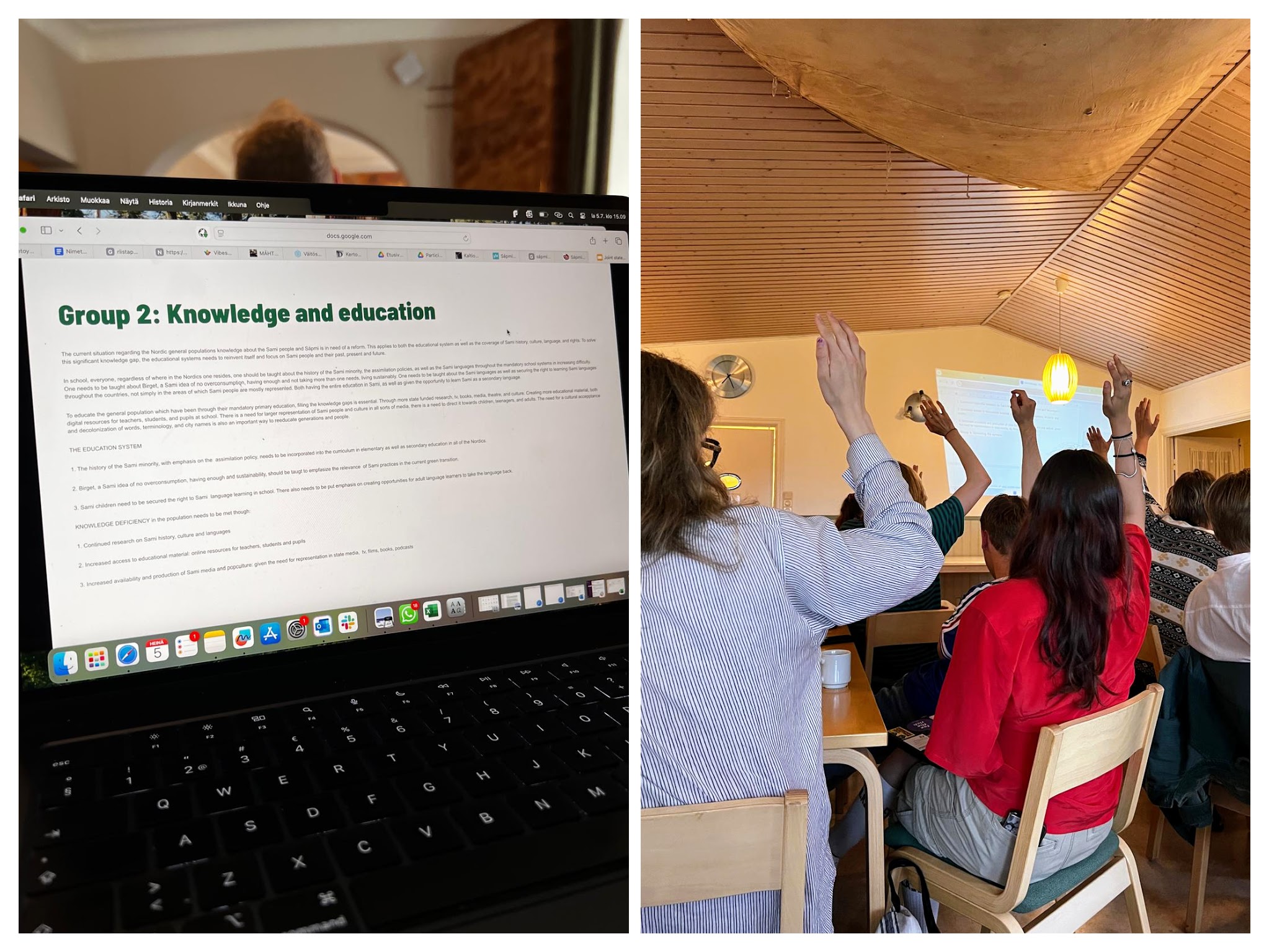

Working on the joint statement.In addition to informative lectures and a panel discussion, we also had the opportunity to work on a joint statement during the event. The large number of participants, the multifaceted topic, and the fatigue caused by intensive learning presented their own challenges. Nevertheless, through working in small groups, we managed to produce drafts on the content of various sub-themes, which were further developed through joint comments and the reorganisation of the groups. Later in the evening, we were able to vote on the amendments made, and the event’s working group will produce a final draft based on the work done during the day.

All in all, the trip to Åland was an informative and intensive experience. It is clear that work must be done at both the state and Nordic cooperation levels to realize the rights of the Sámi people. Sharing information is an important part of this process, and the camp in Åland was a step in the right direction. We are now continuing this work in Akordi, among other things in the form of the above-mentioned FPIC-focused training day in September, about which more information will be available later (in Finnish).

Many thanks to the organisers for making it possible to participate in this event!

Read Eleonora Alariesto’s essay published in Kaltio magazine, Clean wind power and dirty Sami people (in Finnish).

The author is Akordi’s project worker Sara Vanhanen, who discussed the wind power conflict in Fosen, Norway, through the lens of ontological conflict and green extractivism in her master’s thesis. Read Sara’s thesis here.